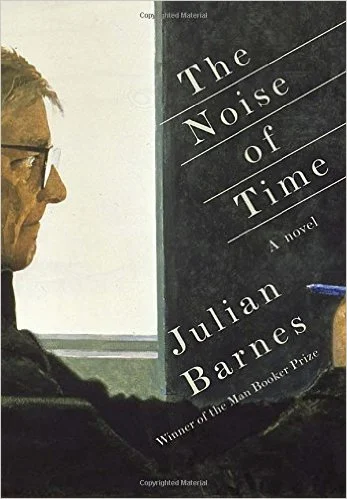

Alfred A. Knopf New York, 2016

“Muddle Instead of Music” is a statement that belongs to the well-known editorial denunciation of the opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District by Dmitri Shostakovich, which made the front page of Pravda in 1936. Up to that point, the thirty year-old composer was gaining increased success in the Soviet Union and abroad. Speculation about who actually wrote this scathing review ranges from Joseph Stalin to high-ranking officials from the Union of Composers. Needless to say, Shostakovichs’ career was virtually on hold until Soviet authorities decided to welcome this musical genius back into the fold – but their push pull ideological grip of intimidation continued until his death in 1975.

The Noise of Time, a recent book by Julian Barnes, offers a collage of events in the life of Dmitri Shostakovich with dark and probing intensity. Barnes’ up close and personal writing is peppered with expressive and often hard-hitting descriptions of this composer’s interaction with situations such as family, Stalin, notable friends, Stravinsky, Khachaturian, Kabalevsky, Khrennikov, and participation at cultural congresses in New York. And there are colorful descriptions of his wartime travels, cigarette smoking, vodka drinking, affaire d’amour and disappointment at being allowed to drive only Russian made automobiles unlike Prokofiev and Rostropovich.

What is most compelling is the author’s attempt to delve into the mind, emotions and soul of Shostakovich to create the impression that one might have known him, if one already did not. In this regard, the author credits Elizabeth Wilson’s book, Shostakovich: A Life Remembered (Princeton University Press, 1994) and Testimony The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich by Solomon Volkov (Limelight Editions, 1979) as among valuable source material. Yet Barnes writes in the Author’s Note section, “But this is my book not hers {Elizabeth Wilson}; and if you haven’t liked mine, then read hers.”

Much of the content in Volkov’s book has been discredited, but Barnes’ approach is more plausible in its desire to provide insight about Shostakovichs’ idiosyncratic nature, neurotic tendencies, love for motherland and dedication to artistic and humanistic principles – while residing in a regime of control freaks who saturated him with praise and ridicule as an enemy of the people.

Barnes relates a story about how Russian audiences would listen to Shostakovich’s Six Romances on Verses by English Poets, Op. 140 and when Shakespeare’s Sonnet 66 was sung, softly speak or mouth the words, “And art made tongue-tied by authority.” While this statement contains an essence of what The Noise of Time is all about, I think the best way of understanding Shostakovichs’ creatively complex persona is to listen to his music and there is so much to absorb: film scores, fifteen symphonies and string quartets, The Nose and some of the most sublime melodies you will ever hear in the Andante of his second piano concerto, Op. 102.